- Turn web content into useful data. Scrapinghub has 184 repositories available. Follow their code on GitHub.

- The Jupyter Notebook is an open source web application that you can use to create and share documents that contain live code, equations, visualizations, and text. Jupyter Notebook is maintained by the people at Project Jupyter. Jupyter Notebooks are a spin-off project from the IPython project, which used to have an IPython Notebook project itself.

- What Is Jupyter Notebook

- Web Scraping Jupiter Notebook Tutorial

- Jupyter Notebook Web

- Jupyter Notebook App

Running the jupyter notebook with anaconda powershell. Here you can see that the default working folder of Jupyter notebook was c: user Dibyendu as in the PowerShell. I have changed the directory to E: and simply run the command jupyter notebook. Consequently, PowerShell has run the Jupyter notebook with the start folder as mentioned.

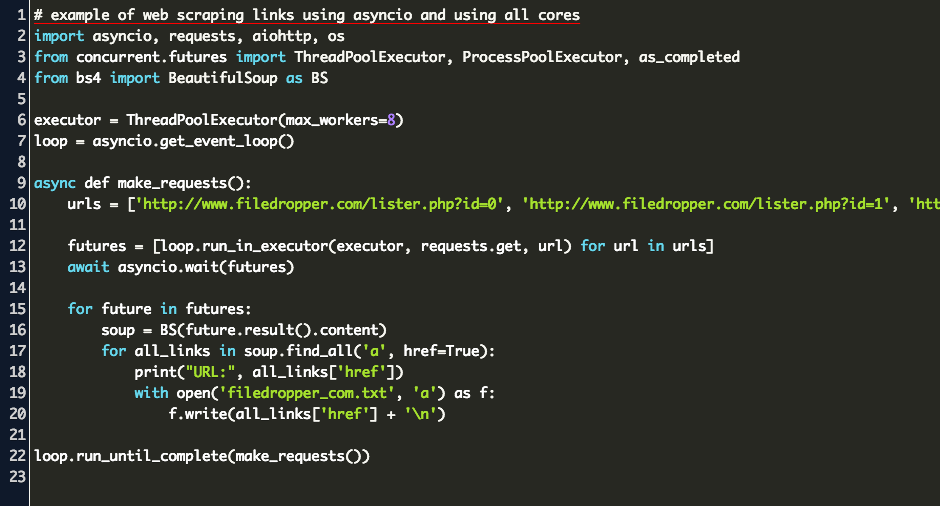

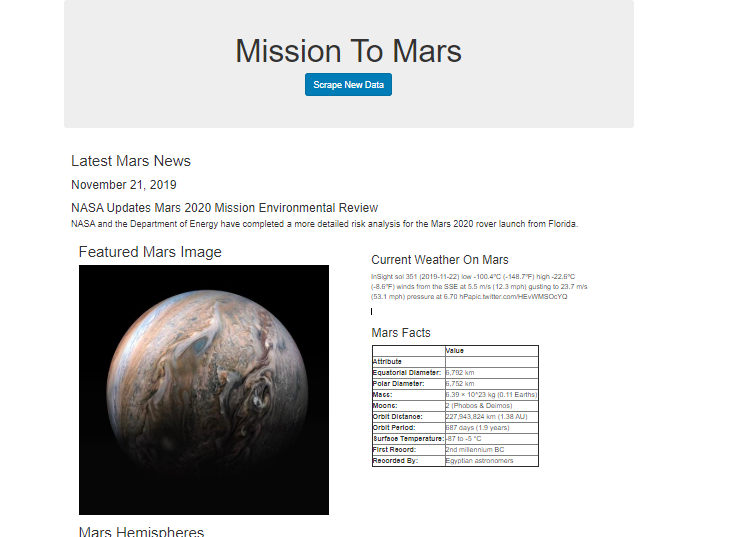

In this tutorial we will use a technique called web scraping to extract data from a website.

We’ll be using Python 3.7 through a Jupyter Notebook on Anaconda and the Python libraries urllib, BeautifulSoup and Pandas.

(If you don’t have Anaconda or Jupyter Notebook installed on your Windows machine, check out our tutorial How Do I Install Anaconda On Windows? before getting started. If you’re on Linux or Mac OS X you’ll have to Google it. Bill Gates fanboy in the house.…)

What is Web Scraping?

Web scraping (also known as screen scraping, data scraping, web harvesting, web data extraction and a multitude of other aliases) is a method for extracting data from web pages.

I’ve done a quick primer on WTF Is…Web Scraping to get you up to speed on what it is and why we might use it. Have a quick read and re-join the tour group as soon as possible.

Step By Step Tutorial

OK. Now we know what web scraping is and why we might have to use it to get data out of a website.

How exactly do we get started scraping and harvesting all of that delicious data for our future perusal and use?

Standing on the shoulders of giants.

When I first tried screen scraping with Python I used an earlier version of it and worked through Sunil Ray’s Beginner’s Guide on the Analytics Vidhya blog.

Working with Python 3.7 now I had to change some libraries plus do a few further corrective steps for the data I’m looking to get hence not just pointing you straight to that article.

Which Python libraries will we be using for web scraping?

Urllib.request

As we are using Python 3.7, we will use urllib.request to fetch the HTML from the URL we specify that we want to scrape.

BeautifulSoup

Once urllib.request has pulled in the content from the URL, we use the power of BeautifulSoup to extract and work with the data within it. BeautifulSoup4 has a multitude of functions at it’s disposal to make this incredibly easy for us.

Learn more about Beautiful Soup.

Anything else we need to know before we kick this off?

Are you familiar with HTML?

HTML (Hypertext Markup Language) is the standard markup langauge for creating web pages. It consists of a collection of tags which represent HTML elements. These elements combined tell your web browser what the structure of the web page looks like. In this tutorial we will mostly be concerned with the HTML table tags as our data is contained in a table. For more reading on HTML, check out W3Schools Introduction to HTML.

Right, let’s get into it.

1. Open a new Jupyter notebook.

You do have it installed, don’t you? You didn’t just skip the advice at the top, did you? If so, go back and get that done then come back to this point.

2. Choosing our target Wikipedia page.

Like our friend Sunil, we are going to scrape some data from a Wikipedia page. While he was interested in state capitals in India, I’ve decided to pick a season at random from the English Premier League, namely the 1999/2000 season.

When I went and looked at the page I instantly regretted picking this season (fellow Tottenham Hotspur fans will understand why when they see the manager and captain at the end but I’ll stick with it as some kind of sado-masochism if nothing else).

3. Import urllib library.

Firstly, we need to import the library we will be using to connect to the Wikipedia page and fetch the contents of that page:

Next we specify the URL of the Wikipedia page we are looking to scrape:

Using the urllib.request library, we want to query the page and put the HTML data into a variable (which we have called ‘url’):

4. Import BeautifulSoup library.

Next we want to import the functions from Beautiful Soup which will let us parse and work with the HTML we fetched from our Wiki page:

Then we use Beautiful Soup to parse the HTML data we stored in our 'url' variable and store it in a new variable called ‘soup’ in the Beautiful Soup format. Jupyter Notebook prefers we specify a parser format so we use the “lxml” library option:

5. Take a look at our underlying HTML code.

To get an idea of the structure of the underlying HTML in our web page, we can view the code in two ways: a) right click on the web page itself and click View Source or b) use Beautiful Soup’s prettify function and check it out right there in our Jupyter Notebook.

Let’s see what prettify() gives us:

6. Find the table we want.

By looking at our Wikipedia page for the 1999/2000 Premier League season, we can see there is a LOT of information in there. From a written synopsis of the season to specific managerial changes, we have a veritable treasure trove of data to mine.

What we are going to go for though is the table which shows the personnel and kits for each Premier League club. It’s already set up in nice rows and columns which should make our job a little easier as beginner web scrapers.

Let’s have a look for it in our prettifyed HTML:

And there it is. (NB. since I first wrote this tutorial, Wiki has added another table with satadium name, capacity etc. that also has this class identifier. We'll allow for that further down in the code.)

Starting with an HTML <table> tag with a class identifier of 'wikitable sortable'. We’ll make a note of that for further use later.

Scroll down a little to see how the table is made up and you’ll see the rows start and end with <tr> and </tr> tags.

The top row of headers has <th> tags while the data rows beneath for each club has <td> tags. It’s in these <td> tags that we will tell Python to extract our data from.

7. Some fun with BeautifulSoup functions.

Before we get to that, let’s try out a few Beautiful Soup functions to illustrate how it captures and is able to return data to us from the HTML web page.

If we use the title function, Beautiful Soup will return the HTML tags for the title and the content between them. Specify the string element of 'title' and it gives us just the content string between the tags:

8. Bring back ALL of the tables.

We can use this knowledge to start planning our attack on the HTML and homing in only on the table of personnel and kit information that we want to work with on the page.

We know the data resides within an HTML table so firstly we send Beautiful Soup off to retrieve all instances of the <table> tag within the page and add them to an array called all_tables:

Looking through the output of 'all_tables' we can again see that the class id of our chosen table is 'wikitable sortable'. We can use this to get BS to only bring back the table data for this particular table and keep that in a variable called 'right_table'. As I said above, there is now another table with this classname in the HTML, we're going to use find_all to bring back an array and then look for the second element in the array which we know is the table we want:

9. Ignore the headers, find the rows.

Now it starts to get a little more technical. We know that the table is set up in rows (starting with <tr> tags) with the data sitting within <td> tags in each row. We aren't too worried about the header row with the <th> elements as we know what each of the columns represent by looking at the table.

To step things up a notch we could have set BeautifulSoup to find the <th> tags and assigned the contents of each to a variable for future use.

We’ve got enough to get getting on with getting the actual data though so let’s crack on.

10. Loop through the rows.

We know we have to start looping through the rows to get the data for every club in the table. The table is well structured with each club having it's own defined row. This makes things somewhat easier.

There are five columns in our table that we want to scrape the data from so we will set up five empty lists (A, B, C, D and E) to store our data in.

To start with, we want to use the Beautiful Soup 'find_all' function again and set it to look for the string 'tr'. We will then set up a FOR loop for each row within that array and set Python to loop through the rows, one by one.

Within the loop we are going to use find_all again to search each row for <td> tags with the 'td' string. We will add all of these to a variable called 'cells' and then check to make sure that there are 5 items in our 'cells' array (i.e. one for each column).

If there are then we use the find(text=True)) option to extract the content string from within each <td> element in that row and add them to the A-E lists we created at the start of this step. Let’s have a look at the code:

Still with me? Good. This all should work perfectly, shouldn’t it?

We're looping through each row, picking out the <td> tags and plucking the contents from each into a list.

Bingo. This is an absolute gift. Makes you wonder why people make such a fuss about it, doesn’t it?

11. Introducing pandas and dataframes.

To see what our loop through the Personnel and Kits table has brought us back, we need to bring in another big hitter of the Python library family – Pandas. Pandas lets us convert lists into dataframes which are 2 dimensional data structures with rows and columns, very much like spreadsheets or SQL tables.

We’ll import pandas and create a dataframe with it, assigning each of the lists A-E into a column with the name of our source table columns i.e. Team, Manager, Captain, Kit_Manufacturer and Shirt_Sponsor.

Let’s run the Pandas code and see what our table looks like:

Hmmm. That’s not what we wanted. Where's the Manager and Captain data?

Clearly something went wrong in those cells so we need to go back to our HTML to see what the problem is.

12. Searching for the problem.

Looking at our HTML, there does indeed seem to be something a little different about the Manager and Captain data within the <td> tags. Wikipedia has (very helpfully/unhelpfully) added a little flag within <span> tags to help display the nationality of the Managers and Captains in question.

It sure looks nice on the Wiki page but it's messing up my screen-scraping tutorial so I'm somewhat less than happy to have it in there.

Using the knowledge we've gained above, is there a simple way to workaround this problem and just lift out the Manager and Captain names as we planned?

This is how I decided to do it.

Looking at the HTML code, I can see that there are two sets of <a> tags i.e. hyperlinks within each cell for both the Manager and Captain data. The first is a link over the flag’s <img> tag and the second is a link on the Manager/Captain’s name.

If we can get the content string between the <a> and </a> tags on the SECOND of those, we have got the data we need.

I did a 'find_all' within the individual cells to look for the <a> tags and assign that to a variable (mlnk for Managers, clnk for Captains). I knew it was the second <a> tag's content string that I needed to get the name of the Manager and the Captain so I appended the content of the second element in the mlnk/clnk array I had created to the specific list (list B for Managers, list C for Captains).

As so:

Now run that and re-run our pandas code from before and 'hopefully' we'll fill in those blanks from the previous output:

Hurrah!

We now have 20 rows for the 20 clubs with columns for Team Name, Manager, Captain, Kit Manufacturer and Shirt Sponsor. Just like we always wanted.

(I’ll ignore the names in the Manager and Captain columns for Tottenham, must research my examples better before getting started…)

Want an even easier way to do this using just pandas?

Eternal thanks to reader Lynn Leifker who has sent me an even quicker and easier way to scrape HTML tables using only pandas. You'll still have to do some HTML investigation to find which table in the overall page code you are looking for but can get to the outcome quicker using this code:

Hurrah once again and a big thanks to Lynn for the top tip!

Wrapping Up

That successful note brings us to the end of our Getting Started Web Scraping with Python tutorial. Hopefully it gives you enough to get working on to try some scraping out for yourself. We've introduced urllib.request to fetch the URL and HTML data, Beautiful Soup to parse the HTML and Pandas to transform the data into a dataframe for presentation.

We also saw that things don't always work out just as easily as we hope for when working with web pages but it’s best to roll with the punches and come up with a plan to workaround it as simply as possible,

If you have any questions, please send me a mail (alan AT alanhylands DOT com). Happy scraping but if you get caught…we never met!

Part one of this series focuses on requesting and wrangling HTML using two of the most popular Python libraries for web scraping: requests and BeautifulSoup

After the 2016 election I became much more interested in media bias and the manipulation of individuals through advertising. This series will be a walkthrough of a web scraping project that monitors political news from both left and right wing media outlets and performs an analysis on the rhetoric being used, the ads being displayed, and the sentiment of certain topics.

The first part of the series will we be getting media bias data and focus on only working locally on your computer, but if you wish to learn how to deploy something like this into production, feel free to leave a comment and let me know.

You should already know:

- Python fundamentals - lists, dicts, functions, loops - learn on Coursera

- Basic HTML

You will have learned:

- Requesting web pages

- Parsing HTML

- Saving and loading scraped data

- Scraping multiple pages in a row

Every time you load a web page you're making a request to a server, and when you're just a human with a browser there's not a lot of damage you can do. With a Python script that can execute thousands of requests a second if coded incorrectly, you could end up costing the website owner a lot of money and possibly bring down their site (see Denial-of-service attack (DoS)).

With this in mind, we want to be very careful with how we program scrapers to avoid crashing sites and causing damage. Every time we scrape a website we want to attempt to make only one request per page. We don't want to be making a request every time our parsing or other logic doesn't work out, so we need to parse only after we've saved the page locally.

If I'm just doing some quick tests, I'll usually start out in a Jupyter notebook because you can request a web page in one cell and have that web page available to every cell below it without making a new request. Since this article is available as a Jupyter notebook, you will see how it works if you choose that format.

After we make a request and retrieve a web page's content, we can store that content locally with Python's open() function. To do so we need to use the argument wb, which stands for 'write bytes'. This let's us avoid any encoding issues when saving.

Below is a function that wraps the open() function to reduce a lot of repetitive coding later on:

Assume we have captured the HTML from google.com in html, which you'll see later how to do. After running this function we will now have a file in the same directory as this notebook called google_com that contains the HTML.

To retrieve our saved file we'll make another function to wrap reading the HTML back into html. We need to use rb for 'read bytes' in this case.

The open function is doing just the opposite: read the HTML from google_com. If our script fails, notebook closes, computer shuts down, etc., we no longer need to request Google again, lessening our impact on their servers. While it doesn't matter much with Google since they have a lot of resources, smaller sites with smaller servers will benefit from this.

I save almost every page and parse later when web scraping as a safety precaution.

Each site usually has a robots.txt on the root of their domain. This is where the website owner explicitly states what bots are allowed to do on their site. Simply go to example.com/robots.txt and you should find a text file that looks something like this:

The User-agent field is the name of the bot and the rules that follow are what the bot should follow. Some robots.txt will have many User-agents with different rules. Common bots are googlebot, bingbot, and applebot, all of which you can probably guess the purpose and origin of.

We don't really need to provide a User-agent when scraping, so User-agent: * is what we would follow. A * means that the following rules apply to all bots (that's us).

The Crawl-delay tells us the number of seconds to wait before requests, so in this example we need to wait 10 seconds before making another request.

Allow gives us specific URLs we're allowed to request with bots, and vice versa for Disallow. In this example we're allowed to request anything in the /pages/subfolder which means anything that starts with example.com/pages/. On the other hand, we are disallowed from scraping anything from the /scripts/subfolder.

Many times you'll see a * next to Allow or Disallow which means you are either allowed or not allowed to scrape everything on the site.

Sometimes there will be a disallow all pages followed by allowed pages like this:

This means that you're not allowed to scrape anything except the subfolder /pages/. Essentially, you just want to read the rules in order where the next rule overrides the previous rule.

This project will primarily be run through a Jupyter notebook, which is done for teaching purposes and is not the usual way scrapers are programmed. After showing you the pieces, we'll put it all together into a Python script that can be run from command line or your IDE of choice.

With Python's requests (pip install requests) library we're getting a web page by using get() on the URL. The response r contains many things, but using r.content will give us the HTML. Once we have the HTML we can then parse it for the data we're interested in analyzing.

There's an interesting website called AllSides that has a media bias rating table where users can agree or disagree with the rating.

Since there's nothing in their robots.txt that disallows us from scraping this section of the site, I'm assuming it's okay to go ahead and extract this data for our project. Let's request the this first page:

Since we essentially have a giant string of HTML, we can print a slice of 100 characters to confirm we have the source of the page. Let's start extracting data.

What does BeautifulSoup do?

We used requests to get the page from the AllSides server, but now we need the BeautifulSoup library (pip install beautifulsoup4) to parse HTML and XML. When we pass our HTML to the BeautifulSoup constructor we get an object in return that we can then navigate like the original tree structure of the DOM.

This way we can find elements using names of tags, classes, IDs, and through relationships to other elements, like getting the children and siblings of elements.

We create a new BeautifulSoup object by passing the constructor our newly acquired HTML content and the type of parser we want to use:

This soup object defines a bunch of methods — many of which can achieve the same result — that we can use to extract data from the HTML. Let's start with finding elements.

To find elements and data inside our HTML we'll be using select_one, which returns a single element, and select, which returns a list of elements (even if only one item exists). Both of these methods use CSS selectors to find elements, so if you're rusty on how CSS selectors work here's a quick refresher:

A CSS selector refresher

- To get a tag, such as

<a></a>,<body></body>, use the naked name for the tag. E.g.select_one('a')gets an anchor/link element,select_one('body')gets the body element .tempgets an element with a class of temp, E.g. to get<a></a>useselect_one('.temp')#tempgets an element with an id of temp, E.g. to get<a></a>useselect_one('#temp').temp.examplegets an element with both classes temp and example, E.g. to get<a></a>useselect_one('.temp.example').temp agets an anchor element nested inside of a parent element with class temp, E.g. to get<div><a></a></div>useselect_one('.temp a'). Note the space between.tempanda..temp .examplegets an element with class example nested inside of a parent element with class temp, E.g. to get<div><a></a></div>useselect_one('.temp .example'). Again, note the space between.tempand.example. The space tells the selector that the class after the space is a child of the class before the space.- ids, such as

<a id=one></a>, are unique so you can usually use the id selector by itself to get the right element. No need to do nested selectors when using ids.

There's many more selectors for for doing various tasks, like selecting certain child elements, specific links, etc., that you can look up when needed. The selectors above get us pretty close to everything we would need for now.

Tips on figuring out how to select certain elements

Most browsers have a quick way of finding the selector for an element using their developer tools. In Chrome, we can quickly find selectors for elements by

- Right-click on the the element then select 'Inspect' in the menu. Developer tools opens and and highlights the element we right-clicked

- Right-click the code element in developer tools, hover over 'Copy' in the menu, then click 'Copy selector'

Sometimes it'll be a little off and we need to scan up a few elements to find the right one. Here's what it looks like to find the selector and Xpath, another type of selector, in Chrome:

Our data is housed in a table on AllSides, and by inspecting the header element we can find the code that renders the table and rows. What we need to do is select all the rows from the table and then parse out the information from each row.

Here's how to quickly find the table in the source code:

Simplifying the table's HTML, the structure looks like this (comments <!-- --> added by me):

So to get each row, we just select all <tr> inside <tbody>:

tbody tr tells the selector to extract all <tr> (table row) tags that are children of the <tbody> body tag. If there were more than one table on this page we would have to make a more specific selector, but since this is the only table, we're good to go.

Now we have a list of HTML table rows that each contain four cells:

- News source name and link

- Bias data

- Agreement buttons

- Community feedback data

Below is a breakdown of how to extract each one.

The outlet name (ABC News) is the text of an anchor tag that's nested inside a <td> tag, which is a cell — or table data tag.

Getting the outlet name is pretty easy: just get the first row in rows and run a select_one off that object:

The only class we needed to use in this case was .source-title since .views-field looks to be just a class each row is given for styling and doesn't provide any uniqueness.

Notice that we didn't need to worry about selecting the anchor tag a that contains the text. When we use .text is gets all text in that element, and since 'ABC News' is the only text, that's all we need to do. Bear in mind that using select or select_one will give you the whole element with the tags included, so we need .text to give us the text between the tags.

.strip() ensures all the whitespace surrounding the name is removed. Many websites use whitespace as a way to visually pad the text inside elements so using strip() is always a good idea.

You'll notice that we can run BeautifulSoup methods right off one of the rows. That's because the rows become their own BeautifulSoup objects when we make a select from another BeautifulSoup object. On the other hand, our name variable is no longer a BeautifulSoup object because we called .text.

We also need the link to this news source's page on AllSides. If we look back at the HTML we'll see that in this case we do want to select the anchor in order to get the href that contains the link, so let's do that:

It is a relative path in the HTML, so we prepend the site's URL to make it a link we can request later.

Getting the link was a bit different than just selecting an element. We had to access an attribute (href) of the element, which is done using brackets, like how we would access a Python dictionary. This will be the same for other attributes of elements, like src in images and videos.

We can see that the rating is displayed as an image so how can we get the rating in words? Looking at the HTML notice the link that surrounds the image has the text we need:

We could also pull the alt attribute, but the link looks easier. Let's grab it:

Here we selected the anchor tag by using the class name and tag together: .views-field-field-bias-image is the class of the <td> and <a> is for the anchor nested inside.

After that we extract the href just like before, but now we only want the last part of the URL for the name of the bias so we split on slashes and get the last element of that split (left-center).

The last thing to scrape is the agree/disagree ratio from the community feedback area. The HTML of this cell is pretty convoluted due to the styling, but here's the basic structure:

The numbers we want are located in two span elements in the last div. Both span elements have classes that are unique in this cell so we can use them to make the selection:

Using .text will return a string, so we need to convert them to integers in order to calculate the ratio.

Side note: If you've never seen this way of formatting print statements in Python, the f at the front allows us to insert variables right into the string using curly braces. The :.2f is a way to format floats to only show two decimals places.

If you look at the page in your browser you'll notice that they say how much the community is in agreement by using 'somewhat agree', 'strongly agree', etc. so how do we get that? If we try to select it:

It shows up as None because this element is rendered with Javascript and requests can't pull HTML rendered with Javascript. We'll be looking at how to get data rendered with JS in a later article, but since this is the only piece of information that's rendered this way we can manually recreate the text.

To find the JS files they're using, just CTRL+F for '.js' in the page source and open the files in a new tab to look for that logic.

It turned out the logic was located in the eleventh JS file and they have a function that calculates the text and color with these parameters:

| Range | Agreeance |

| $ratio > 3$ | absolutely agrees |

| $2 < ratio leq 3$ | strongly agrees |

| $1.5 < ratio leq 2$ | agrees |

| $1 < ratio leq 1.5$ | somewhat agrees |

| $ratio = 1$ | neutral |

| $0.67 < ratio < 1$ | somewhat disgrees |

| $0.5 < ratio leq 0.67$ | disgrees |

| $0.33 < ratio leq 0.5$ | strongly disagrees |

| $ratio leq 0.33$ | absolutely disagrees |

Now that we have the general logic for a single row and we can generate the agreeance text, let's create a loop that gets data from every row on the first page:

In the loop we can combine any multi-step extractions into one to create the values in the least number of steps.

Our data list now contains a dictionary containing key information for every row.

What Is Jupyter Notebook

Keep in mind that this is still only the first page. The list on AllSides is three pages long as of this writing, so we need to modify this loop to get the other pages.

Notice that the URLs for each page follow a pattern. The first page has no parameters on the URL, but the next pages do; specifically they attach a ?page=#to the URL where '#' is the page number.

Right now, the easiest way to get all pages is just to manually make a list of these three pages and loop over them. If we were working on a project with thousands of pages we might build a more automated way of constructing/finding the next URLs, but for now this works.

According to AllSides' robots.txt we need to make sure we wait ten seconds before each request.

Our loop will:

- request a page

- parse the page

- wait ten seconds

- repeat for next page.

Remember, we've already tested our parsing above on a page that was cached locally so we know it works. You'll want to make sure to do this before making a loop that performs requests to prevent having to reloop if you forgot to parse something.

By combining all the steps we've done up to this point and adding a loop over pages, here's how it looks:

Now we have a list of dictionaries for each row on all three pages.

To cap it off, we want to get the real URL to the news source, not just the link to their presence on AllSides. To do this, we will need to get the AllSides page and look for the link.

If we go to ABC News' page there's a row of external links to Facebook, Twitter, Wikipedia, and the ABC News website. The HTML for that sections looks like this:

Notice the anchor tag (<a>) that contains the link to ABC News has a class of 'www'. Pretty easy to get with what we've already learned:

So let's make another loop to request the AllSides page and get links for each news source. Unfortunately, some pages don't have a link in this grey bar to the news source, which brings up a good point: always account for elements to randomly not exist.

Up until now we've assumed elements exist in the tables we scraped, but it's always a good idea to program scrapers in way so they don't break when an element goes missing.

Using select_one or select will always return None or an empty list if nothing is found, so in this loop we'll check if we found the website element or not so it doesn't throw an Exception when trying to access the href attribute.

Finally, since there's 265 news source pages and the wait time between pages is 10 seconds, it's going to take ~44 minutes to do this. Instead of blindly not knowing our progress, let's use the tqdm library (pip install tqdm) to give us a nice progress bar:

tqdm is a little weird at first, but essentially tqdm_notebook is just wrapping around our data list to produce a progress bar. We are still able to access each dictionary, d, just as we would normally. Note that tqdm_notebook is only for Jupyter notebooks. In regular editors you'll just import tqdm from tqdm and use tqdm instead.

So what do we have now? At this moment, data is a list of dictionaries, each of which contains all the data from the tables as well as the websites from each individual news source's page on AllSides.

The first thing we'll want to do now is save that data to a file so we don't have to make those requests again. We'll be storing the data as JSON since it's already in that form anyway:

If you're not familiar with JSON, just quickly open allsides.json in an editor and see what it looks like. It should look almost exactly like what data looks like if we print it in Python: a list of dictionaries.

Before ending this article I think it would be worthwhile to actually see what's interesting about this data we just retrieved. So, let's answer a couple of questions.

Which ratings for outlets does the communityabsolutely agreeon?

To find where the community absolutely agrees we can do a simple list comprehension that checks each dict for the agreeance text we want:

Using some string formatting we can make it look somewhat tabular. Interestingly, C-SPAN is the only center bias that the community absolutely agrees on. The others for left and right aren't that surprising.

Which ratings for outlets does the communityabsolutely disagreeon?

To make analysis a little easier, we can also load our JSON data into a Pandas DataFrame as well. This is easy with Pandas since they have a simple function for reading JSON into a DataFrame.

As an aside, if you've never used Pandas (pip install pandas), Matplotlib (pip install matplotlib), or any of the other data science libraries, I would definitely recommend checking out Jose Portilla's data science course for a great intro to these tools and many machine learning concepts.

Now to the DataFrame:

| agree | agree_ratio | agreeance_text | allsides_page | bias | disagree | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| name | ||||||

| ABC News | 8355 | 1.260371 | somewhat agrees | https://www.allsides.com/news-source/abc-news-... | left-center | 6629 |

| Al Jazeera | 1996 | 0.694986 | somewhat disagrees | https://www.allsides.com/news-source/al-jazeer... | center | 2872 |

| AllSides | 2615 | 2.485741 | strongly agrees | https://www.allsides.com/news-source/allsides-0 | allsides | 1052 |

| AllSides Community | 1760 | 1.668246 | agrees | https://www.allsides.com/news-source/allsides-... | allsides | 1055 |

| AlterNet | 1226 | 2.181495 | strongly agrees | https://www.allsides.com/news-source/alternet | left | 562 |

| agree | agree_ratio | agreeance_text | allsides_page | bias | disagree | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| name | ||||||

| CNBC | 1239 | 0.398905 | strongly disagrees | https://www.allsides.com/news-source/cnbc | center | 3106 |

| Quillette | 45 | 0.416667 | strongly disagrees | https://www.allsides.com/news-source/quillette... | right-center | 108 |

| The Courier-Journal | 64 | 0.410256 | strongly disagrees | https://www.allsides.com/news-source/courier-j... | left-center | 156 |

| The Economist | 779 | 0.485964 | strongly disagrees | https://www.allsides.com/news-source/economist | left-center | 1603 |

| The Observer (New York) | 123 | 0.484252 | strongly disagrees | https://www.allsides.com/news-source/observer | center | 254 |

| The Oracle | 33 | 0.485294 | strongly disagrees | https://www.allsides.com/news-source/oracle | center | 68 |

| The Republican | 108 | 0.392727 | strongly disagrees | https://www.allsides.com/news-source/republican | center | 275 |

It looks like much of the community disagrees strongly with certain outlets being rated with a 'center' bias.

Let's make a quick visualization of agreeance. Since there's too many news sources to plot so let's pull only those with the most votes. To do that, we can make a new column that counts the total votes and then sort by that value:

| agree | agree_ratio | agreeance_text | allsides_page | bias | disagree | total_votes | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| name | |||||||

| CNN (Web News) | 22907 | 0.970553 | somewhat disagrees | https://www.allsides.com/news-source/cnn-media... | left-center | 23602 | 46509 |

| Fox News | 17410 | 0.650598 | disagrees | https://www.allsides.com/news-source/fox-news-... | right-center | 26760 | 44170 |

| Washington Post | 21434 | 1.682022 | agrees | https://www.allsides.com/news-source/washingto... | left-center | 12743 | 34177 |

| New York Times - News | 12275 | 0.570002 | disagrees | https://www.allsides.com/news-source/new-york-... | left-center | 21535 | 33810 |

| HuffPost | 15056 | 0.834127 | somewhat disagrees | https://www.allsides.com/news-source/huffpost-... | left | 18050 | 33106 |

| Politico | 11047 | 0.598656 | disagrees | https://www.allsides.com/news-source/politico-... | left-center | 18453 | 29500 |

| Washington Times | 18934 | 2.017475 | strongly agrees | https://www.allsides.com/news-source/washingto... | right-center | 9385 | 28319 |

| NPR News | 15751 | 1.481889 | somewhat agrees | https://www.allsides.com/news-source/npr-media... | center | 10629 | 26380 |

| Wall Street Journal - News | 9872 | 0.627033 | disagrees | https://www.allsides.com/news-source/wall-stre... | center | 15744 | 25616 |

| Townhall | 7632 | 0.606967 | disagrees | https://www.allsides.com/news-source/townhall-... | right | 12574 | 20206 |

Visualizing the data

To make a bar plot we'll use Matplotlib with Seaborn's dark grid style:

As mentioned above, we have too many news outlets to plot comfortably, so just make a copy of the top 25 and place it in a new df2 variable:

Web Scraping Jupiter Notebook Tutorial

| agree | agree_ratio | agreeance_text | allsides_page | bias | disagree | total_votes | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| name | |||||||

| CNN (Web News) | 22907 | 0.970553 | somewhat disagrees | https://www.allsides.com/news-source/cnn-media... | left-center | 23602 | 46509 |

| Fox News | 17410 | 0.650598 | disagrees | https://www.allsides.com/news-source/fox-news-... | right-center | 26760 | 44170 |

| Washington Post | 21434 | 1.682022 | agrees | https://www.allsides.com/news-source/washingto... | left-center | 12743 | 34177 |

| New York Times - News | 12275 | 0.570002 | disagrees | https://www.allsides.com/news-source/new-york-... | left-center | 21535 | 33810 |

| HuffPost | 15056 | 0.834127 | somewhat disagrees | https://www.allsides.com/news-source/huffpost-... | left | 18050 | 33106 |

With the top 25 news sources by amount of feedback, let's create a stacked bar chart where the number of agrees are stacked on top of the number of disagrees. This makes the total height of the bar the total amount of feedback.

Below, we first create a figure and axes, plot the agree bars, plot the disagree bars on top of the agrees using bottom, then set various text features:

For a slightly more complex version, let's make a subplot for each bias and plot the respective news sources.

This time we'll make a new copy of the original DataFrame beforehand since we can plot more news outlets now.

Instead of making one axes, we'll create a new one for each bias to make six total subplots:

Hopefully the comments help with how these plots were created. We're just looping through each unique bias and adding a subplot to the figure.

When interpreting these plots keep in mind that the y-axis has different scales for each subplot. Overall it's a nice way to see which outlets have a lot of votes and where the most disagreement is. This is what makes scraping so much fun!

We have the tools to make some fairly complex web scrapers now, but there's still the issue with Javascript rendering. This is something that deserves its own article, but for now we can do quite a lot.

There's also some project organization that needs to occur when making this into a more easily runnable program. We need to pull it out of this notebook and code in command-line arguments if we plan to run it often for updates.

These sorts of things will be addressed later when we build more complex scrapers, but feel free to let me know in the comments of anything in particular you're interested in learning about.

Resources

Web Scraping with Python: Collecting More Data from the Modern Web — Book on Amazon

Jose Portilla's Data Science and ML Bootcamp — Course on Udemy

Easiest way to get started with Data Science. Covers Pandas, Matplotlib, Seaborn, Scikit-learn, and a lot of other useful topics.

Get updates in your inbox

Jupyter Notebook Web

Join over 7,500 data science learners.

Jupyter Notebook App

Meet the Authors